Archaeologists find skeletons at Binnengasthuis premises

12 January 2021

Skeletons from 1600

In the past, cemeteries were frequently located near hospitals. The graveyard found at the Binnengasthuis premises predates the Binnengasthuis itself, meaning it was in use around 1600, during the time of the convent and/or the plague house. Maja d’Hollosy's research can offer insight into how people lived at that time, both individually and at the communal level. It is possible to determine whether the people did heavy labour and whether they had a healthy lifestyle or were already suffering from health problems at a young age. Each skeleton will be examined to identify the age, height and gender of the person, as well as any signs of disease or accidents. The manner in which the people were buried also provides insight into the context.

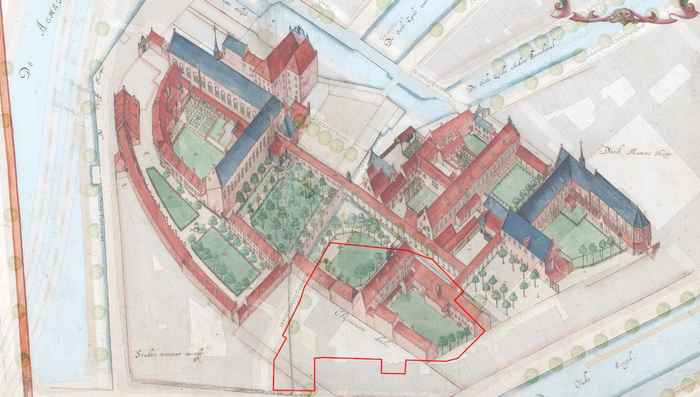

The images below are from Monuments and Archeology, Municipality of Amsterdam.

Click on the photos to enlarge.

Graves and 'knekelkuilen'

The cemetery dates from the period between 1575 and 1625 and is therefore older than the ‘Verbandhuys’ (Bandages House), which served as a department of surgery in the Sint-Pietersgasthuis hospital in 1626. The dig unearthed both graves containing skeletons and pits holding disjointed bones. Only skulls were found in the pits, in this case, while each grave generally contained the remains of a single person. The skeletons of these latter individuals were still articulated, meaning that the bones remained in the correct anatomical positions. The skull, for instance, was found where the head would have been and the lower legs were adjacent to the thigh bones. A lot can happen to a cemetery and its graves after people are buried in them. Bones from numerous people were found in the pits, and these were not articulated. One possible explanation for this is that old graves were cleared away, creating a need to rebury the bones somewhere else. Reburial pits – known as knekelkuilen in Dutch – were dug for this purpose.

A total of eighteen graves containing skeletons were found, five of which belonged to children. The youngest of these was ten years old and the age distribution of the adults appears to have been normal for that period. While more of these formal graves held men than women, in light of the small sample size, this does not necessarily mean anything. The people were buried in wooden coffins.

In the reburial pits, by contrast, only skulls and portions of skulls (such as loose jawbones) were found. Two of these reburial pits were found at the site. One pit contains the remains of twenty individuals, with a more or less equal number of men and women. Eight of the skulls are estimated to have belonged to people between 20 and 40 years of age, and seven skulls were from people aged 40 years or more. Five skulls belonging to children were found as well. The youngest child was nine years old.

There is no significant difference in height between these individuals and remains found in other digs from around the same period. The tallest man was approximately 1.88 metres tall and the shortest man was around 1.65 metres tall. The average height of the men was around 1.71 metres. The women ranged from 1.58 to 1.67 metres tall, with an average height of 1.63 metres.

The images below are from Monuments and Archeology, Municipality of Amsterdam.

Click on the photos to enlarge.

Poor health and rampant poverty

The examination of the skeletal human remains reveals the presence of many diseases and infections. Many of the people suffered from nutritional deficiencies. This can be deduced from evidence such as porous eye sockets, ‘scars’ in the tooth enamel and signs of inflammation of the periosteum, a layer of connective tissue that surrounds bone. Discoloured scars appear on a person's teeth in childhood, meaning the poor living conditions were present from an early age. The overall pathology shows a population afflicted by a combination of poor nutrition and poor health. This is typically associated with poverty.

The research project is a macroscopic study that occasionally involved the use of a magnifying glass. Because only a small group was examined, it is not possible to generate any meaningful statistical results. The practical research is now as good as complete and the definitive report is expected to be finished in mid-2021. Maja d’Hollosy worked in close cooperation with the municipality of Amsterdam's Knowledge Centre for Monuments and Archaeology (MenA).

More information

See also the previous archaeology-related news item. For more information about the new UB, please visit the information page.

MenA published an article on archaeology at Binnengasthuis premises in Erfgoed van de Week (in Dutch).